“Is This What You Were Born To Be?”

December 4, 1994

We begin this morning with some thoughts from a poet named Kenneth Fearing. Several years ago, he wrote a poem called “American Rhapsody.” It was about some people like us who live in a humdrum way – in a fairly predictable routine in an average sort of community. Fearing writes about one particular long and boring day in a woman’s life. When evening comes and the house is quiet, she sits in the family room with her husband, and together they lose themselves in the blur of the television. They have talked a little, but not enough. Trying to make the time pass with a drink and the 10 o’clock news, the woman gets up and says, “It is time for bed. Are you coming?’ “In a minute, ” he replies. But as she heads towards the bedroom, she hears him switch to the late show. She knows there will be another hour of watching, and that she will be dropping off to sleep alone again. Just before she shuts her eyes, she asks herself the question, ‘Did you sometime or somewhere have a different idea?” And then unable to fall asleep, she wonders for the first time in her life: “IS THIS WHAT YOU WERE BORN TO FEEL AND TO DO AND TO BE?”

These are some of the basic questions in life. You cannot get any more basic than to ask what you were born into this world to feel, to do, and to be. I suspect that we are very much like that woman. We rarely find ourselves raising those kinds of questions. But let me raise the issue in a more positive way. How many of us have done some deep reflection and ever dared to say, or feel – “For this I came into the world. For this reason, I was born.”?

As someone said to me the other day, “Roger, you have stopped preaching and started meddling.” And maybe they were right. One of the purposes of a sermon, I believe, is to begin to meddle. We have become as a culture such artful dodgers that we have avoided, at all costs, the really difficult questions such as: ‘What were you born to do and to be?’ We have become very skilled at denial, and so we fool ourselves into thinking basic questions are unimportant. We prefer to live on the surface of life. But every so often, we are caught, and the question comes to mind, ‘What were you born to do and to be?’

Andrew, in our Gospel this morning, had his life pretty well set. He had gone into the family business. For generations, Andrew’s forebears had been fishermen. They earned a good living. They were respected. And there was a strong cultural expectation that children would follow in the footsteps of their fathers. Settling down in the family trade, getting married, producing children, continuing in the same patterns as their parents – the same humdrum existence as everyone else was not only par for the course, but most people were convinced that this was the way that God made the world. It certainly is easier to live on the surface, not making waves, not raising the difficult questions. And so I suppose that Andrew and his friends never bothered to raise some of those deeper questions. We might even suppose that the culture itself never allowed Andrew to question why he was born and for what reason he had come into the world.

Several years ago, a man came into my office and we began to talk. He was ready to retire and had been a dentist for the last 35 years. During our conversation, he said, ‘You know, I’ve always had a dream of becoming a forest ranger, but it just seemed easier and there was more money and security going into dentistry.” After a pause, he said, “Anyway, how can a 23-year-old kid know what will be satisfying at 60? At 23, I never raised any questions. I just went with the flow.”

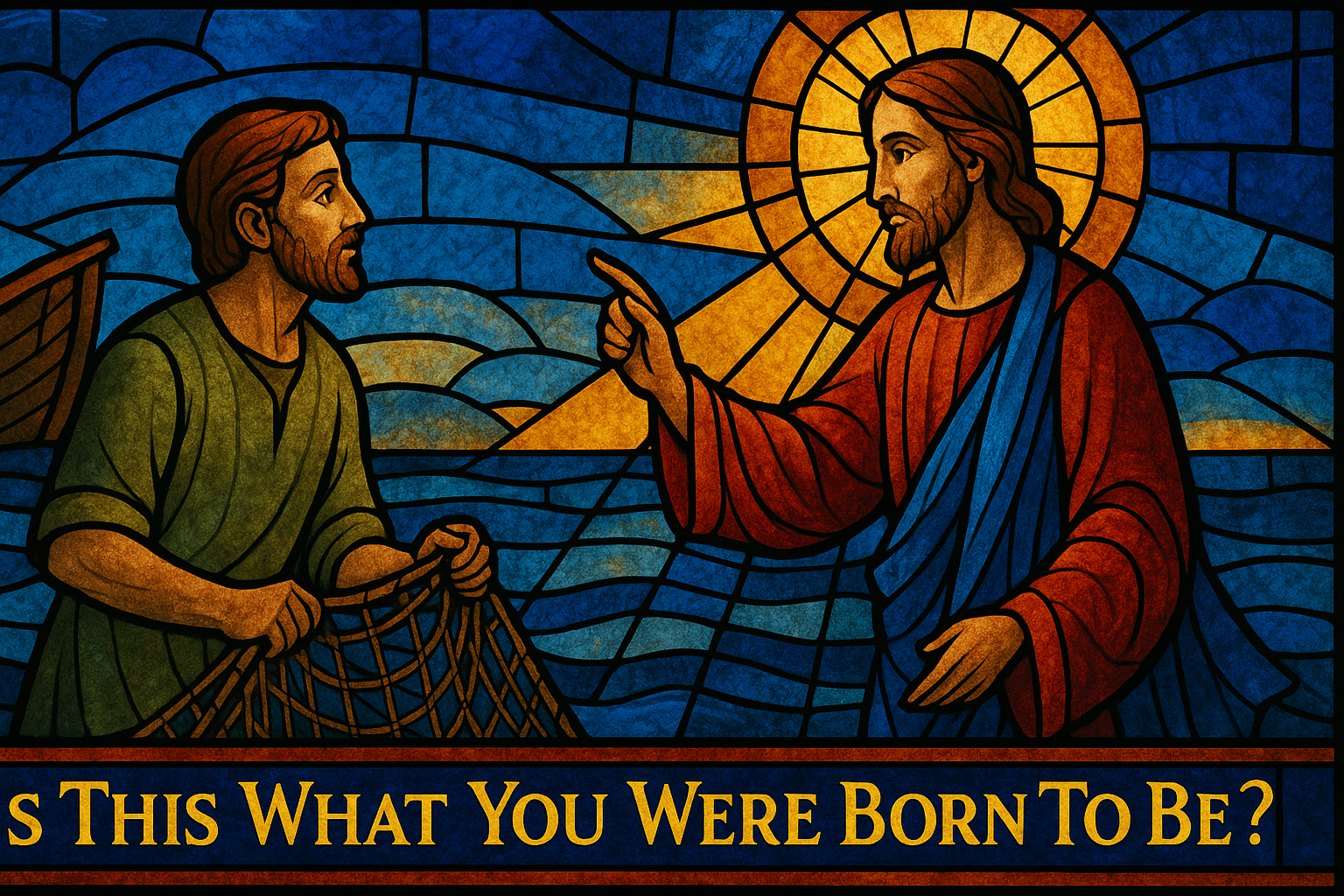

Looking back at Andrew’s story, we are told that Andrew comes upon Jesus, and everything gets turned around. The flow suddenly stopped. We’re not really told much of what happens. All we really can observe is that there is an abrupt change of jobs. In today’s language, we might say Andrew had a career crisis. He suddenly goes from the fishing business to the religious business. But underneath what we are told, I suspect that Jesus confronted Andrew with some of those fundamental questions. I have a hunch he said to Andrew, “Is this what you were born to do and to be? Is this why you came into the world?’

An old friend of mine is a man by the name of Dick Bolles. About 25 years ago, he wrote a book called, ‘What Color is Your Parachute?” It has become a bible for job hunters. If you read the book closely, you will discover that it is not simply a manual for finding a job. It really is a deeply theological book that raises some of the basic questions of life. This shouldn’t surprise us for Dick Bolles is not only a famous job consultant – he is also an Episcopalian priest.

In his book, Bolles says, ‘Before we can ever do very well at finding a job, we have to ask a deeper set of questions: What is my mission? which is a way of saying, What is that unique task that only I can do?” In a secular job search manual, he subtly asks the Jesus question. He puts it this way, “The first part of every person’s mission is to seek and find the One who made us, who gives us our mission. And the second is to be committed to doing whatever we can to make the world a better place. And then, after we have paid attention to both of those, we can ask [ the further question, To what kind of actual work, or task, is my ‘ own unique mission?

But, back again to Andrew. Don’t you wonder what it was that made him do such a turn-around? All his life, all his training, all his associations seemed to dictate that he would follow the fisherman’s trade. And yet suddenly he follows an itinerant rabbi. Suddenly, he gives up a job, a life, that is secure and predictable. Was it the benefit package? Was it the retirement plan? Was it the working conditions? I think not.

I would suggest to you this morning it was Andrew’s discovery that he was called. Somehow, he discovered why he had come into the world. Somehow, Andrew discovered that God was counting upon him to do something special. Somehow, he gained a sense of call. And this knowledge made all the difference.

I sometimes wonder how many of us can say that about our own lives. How many of us feel called out to do something special for God? It has been said that the two most important days in a person’s life are the day on which he was born and the day on which he discovers why he was born. Or, to put it another way, the most important day in a person’s life is the day when he or she finds out that God has a special mission in store for them. Without this discovery, you have lost a certain dimension of magic to your life – a certain dimension of feeling unique – of feeling the mantle of God is upon you and your life.

Remember, it doesn’t really matter how we earn a living. It matters terribly how we earn a life. It doesn’t matter what your job is. It matters terribly that you see your job as doing something special for God. It doesn’t matter what drum you march to. But it matters terribly whether or not Jesus is the drummer.

Listen carefully, listen very carefully this morning. Can you not hear Jesus say, “Christian, follow Me.”

Let me close with part of a meditation from John Henry Newman, the great Anglican priest who later became a Roman Catholic Cardinal. He speaks to those of us who have raised the question as to what we were born to do and to be. Maybe he might speak to you.

“God has created me to do Him some definite service. He has committed some work to me that He has not committed to another. I have my mission. I may never know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next. I am a link in a chain, a bond of connections between persons. He has not created me for naught. . . . therefore I will trust Him. Whatever, whoever I am, I can never be thrown away. If I am in sickness, my sickness may serve Him – in perplexity, my perplexity may serve Him – in sorrow, my sorrow may serve Him. He does nothing in vain. He knows what He is about.”

May I begin to learn what I am about. And then we might add – like Andrew, may we discover why we came into the world, and for what reason we were born.

Amen

“Is This What You Were Born To Be?”

“Is This What You Were Born To Be?”

December 4, 1994