St. Philips Day

May 2, 1999

Recently, I attended a silver anniversary celebration. There were speeches, dinner, and a lot of good cheer. One incident during the speeches stuck with me. The woman, who had introduced the couple, described the attire of the bride on her first date. Her husband disagreed. It reminded me of the scene from the old musical, Gigi. You may remember that the two elderly lovers were singing about the day they met. “I remember it well,” they sing together, ‘Your dress was blue, ” he continues. “No, it was green,” she insists. “I remember it well,” they sing together.

And so it goes, when old friends come together at anniversaries, at family picnics, at class reunions. Often, we’re like the couple in Gigi, and despite our different perceptions, we sing, “I remember it well.”

Keeping alive the memory of our beginnings, of our moments of triumph, and of our times of suffering, is not just an exercise in nostalgia. Memory is important. It tells us who we are and where we’ve been. And that is precisely why we gather at the beginning of May to celebrate our Patron Saint’s Day.

We are here today to remember. Remember from whence we have come. Remember whose name we carry. Remember our roots, our heritage, and our past. Remember Philip, the Saint whose name we bear.

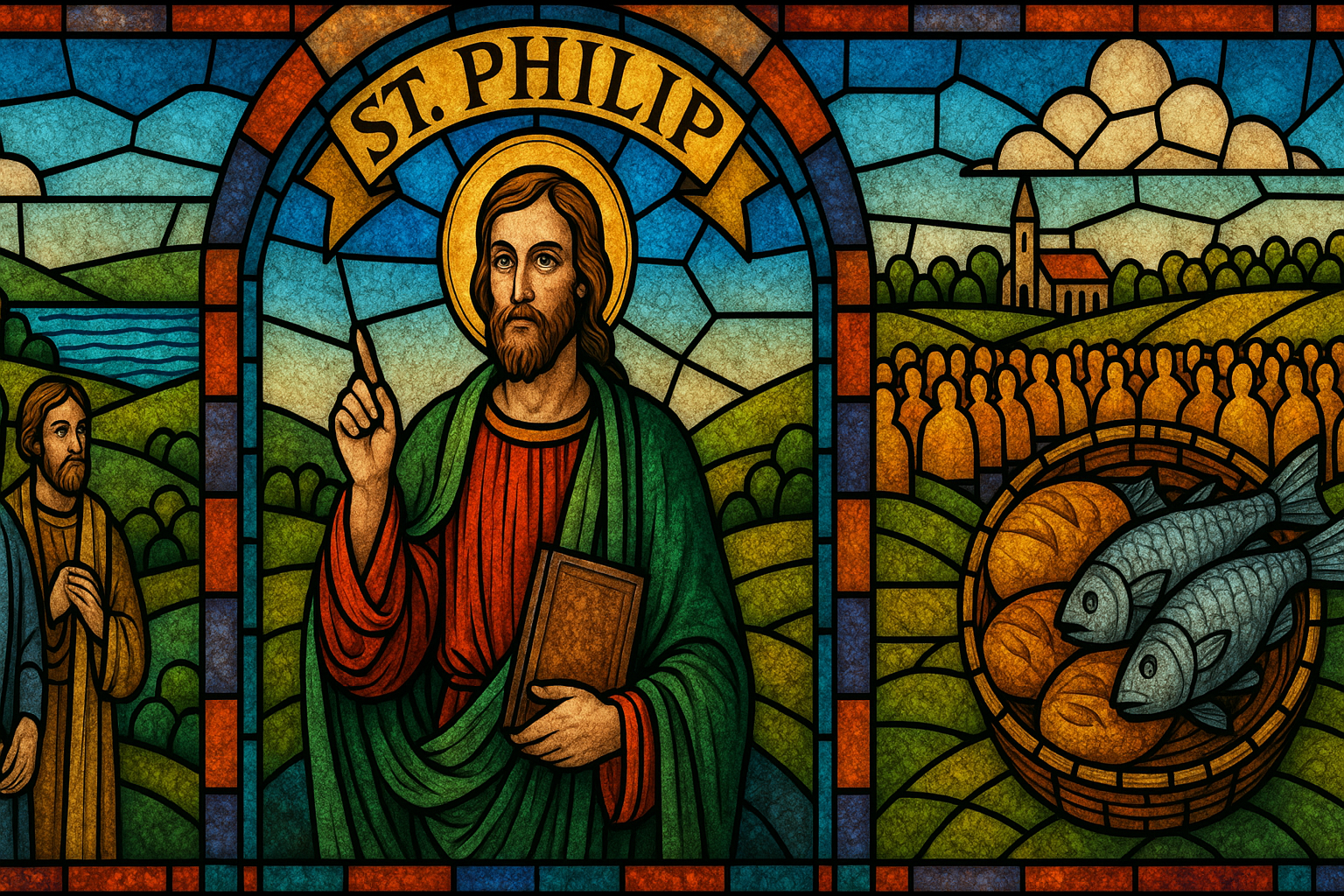

Philip is mentioned three times in the Gospels. First, we hear of him at the start of the ministry of Jesus. Jesus gathers a community of followers, and Philip is one of the original disciples.

When Jesus calls him out, Philip responds by turning to his friend Nathaniel. For this invitation, Philip has to be known as the Patron Saint of introducers.

Do you recall what he said? it wasn’t an argument. “These are the reasons you should join up with Jesus.” It wasn’t an enticement. ‘Accept Jesus and you will become successful or happy, ‘ it was simply an invitation; “Come and see.” No strings attached, no sugar coating, no entitlements. Just reaching out. “Come and see. Just give it a try. Join me, and make up your own mind.” Philip was not very articulate as an evangelist, but without this simple invitation, who knows how the story of Jesus and his disciples would have turned out.

Philip’s spirit of introducing people to Jesus seems to have been lost through the years. We have relegated inviting to the professionals. Episcopalians are some of the worst in this way. I read somewhere that on average, Episcopalians invite a friend or neighbor to go with them to church about once in every 23 years. I know, the excuses are many, but think for a moment how easy it is. All you have to do is to say, “Come and see.” Some of us might be able to do more, but all of us can do as much as Philip did.

The second time we encounter Philip is in the story of the Loaves and Fishes. You’ll recall that there were about 5000 people who had gathered to hear Jesus preach, and it was getting on in the day. A suggestion was made that the crowd be fed. Philip steps up, looks at the resources, and announces that there are only four loaves and a few fish, “but what are they among so many?” Philip here becomes the Patron Saint of cautious church leaders. The Patron Saint of those who count the cost before looking at the opportunities.

I don’t know if the story of the feeding is factual, but this I do know: the learning on that day for Philip was profound. He learned that we live in a world of abundance, not scarcity. And he learned that Jesus can supply our needs; maybe not our wants, but our needs will be met in the kingdom of abundance.

Let me be frank on this our Patron Saint’s day. Most church people start with the practical. Can we afford it? Do we have the resources? And that’s the wrong question. The right question, and the only way to start anything in the kingdom of abundance, is to ask, “What would Jesus have us do?” After forty years in the ministry, I am convinced that the church would be vastly different if we were to start with the Jesus question, and not the resource one, start with abundant thinking, and not scarcity. Start with faith and not safety.

The third and last time we run across Philip is following the Resurrection. The setting is this: The disciples are still in shock. They still haven’t put the events together. Was the Resurrection the beginning of a new day, or the ending of a dream? There were so many questions. For this, he represents the Patron Saint of searchers; those people who are willing to raise the basic religious questions about God. “Show us the Father,” he says. In other words, “Where is God in all this?”

Today, we seem to think those are the kinds of questions that only theologians can raise. Philip, in his naive, blundering way, shows us that the most ordinary among us can raise the deepest issues. Where is God? Where is God in Littleton, Colorado? Where is God in Kosovo, Yugoslavia? Where is God in Tucson, Arizona? Where is God in your life?

The amazing thing is that Jesus responds to Philip by saying,

“Look at me. Look at what I have taught. Look at what I have done, and you will see the Father.”

We who want our religion to be complicated, filled with learned understandings, available to only the most sophisticated among us, are surprised by the response. If you want to see God, look at Jesus. Look at the peasant from Galilee. Look at the dying man on the cross. Look at the one who comes among you. It’s so simple that we often forget. It’s so simple that we often overlook the obvious.

It was 1971, the opening of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington. The center was to be a memorial to a fallen, popular president. A memorial to a man who urged us on to excellence. A center for American culture. A place where the very best in the artistic world would perform. And Leonard Bernstein was commissioned to create something to begin this new era of appreciation of the finest in American culture. Can’t you just imagine the pressure on Bernstein? Do you recall what he wrote? It was called Mass.. And do you remember the first lines? The first lines to be heard at the Kennedy Center began with God. But not the God of the theologians. Not the God of the religious tomes. He began with the God that Jesus called Lauda, which translates to Daddy. This is how Bernstein started, “Sing God a simple song. For God is the simplest of all. God is the simplest of all.”

But back to this day and why we preserve Philip’s memory. The Irish have a word for this process. It’s called (if I can pronounce it) “Greishog.” Gaelic speakers tell me “Greishog” is a process of burying at night, warm coals in ashes in order to preserve the fire for the morning to come. Instead of cleaning out the cold hearth, people preserved yesterday’s glowing coals to start the heating for the next day. This process is extremely important. Otherwise, an entirely new fire must be built every day. The primary concern of “Greishog” is that the fire of the day does not die.

“Greishog,” is not just for coals. It has become a holy process. The preservation of the energy, the warmth, the fire of the past. And this is what we are doing today. We are Greishoging about Philip, keeping alive the memory, so that long after we are gone, the spirit of St. Philip will remain in this place. And then some time in the future, it is our hope that people will be able to say, “I’m proud to bear the name of Philip . . . and will remember-remember.

Amen

St. Philips Day

St. Philips Day

May 2, 1999